Faced with a progressive, incurable illness, I chose not just to follow the standard path, but to ask: what else might help—safely, sustainably, and on my own terms? This article describes the answers I’ve found, and how they have shaped my personal strategy for combatting Parkinson’s Disease. So far, it is producing some positive results for me. However, I must preface it with some important caveats. Parkinson’s is a highly individual condition — no two people experience it in exactly the same way, and what works well for one person may not have the same effect for another. I’m not a medical professional, and nothing in this article should be taken as medical advice. My approach is based on research I’ve conducted, conversations with clinicians and other people with Parkinson’s, and a fair amount of trial and error.

I am following this strategy entirely at my own volition and at my own risk. I’ve made adjustments on an ongoing basis, in view of how my body responds and what feels sustainable for me. If you are considering making any changes to your own treatment or lifestyle, it’s essential to consult with your medical team and ensure that any new strategies are safe and appropriate for your individual situation. That said, I hope that by sharing what I’ve found helpful, others might discover ideas worth exploring in their own journey with Parkinson’s.

Background

My symptoms started to emerge in April 2023, though I didn’t associate them with Parkinson’s until the end of that year. I saw my GP in January 2024, and he commissioned some blood tests and referred me to a specialist at the hospital. I saw the consultant within a few weeks and she believed Parkinson’s was likely, though she commissioned a DAT-scan to be sure. She offered me a drug to stop the tremor in my leg, but I declined (more on that later). The NHS doctors’ strikes throughout 2024 delayed the scan until October. The consultant sent me the results by letter in November, and I met her in early December 2024 to review the scans and discuss the way ahead.

Knowing that I didn’t want to take drugs (at least, not at that stage) she explained that exercise is the only scientifically proven way to slow progress of the disease. The various drugs can moderate symptoms but don’t slow progress. Knowing my academic background and interest in research, she suggested this might be something that I might like to research myself, which I did.

My research surprisingly revealed a number of other potential ways of combatting Parkinson’s without using drugs. However, most of the research was with animal models. Although that research often suggested it needed to be followed up with human studies, there was very little research with people. When I tried to find researchers working in the field, the vast majority were researching the impact of drugs. I guess this is because that is where most of the money is. But this is just going to add to the already burgeoning NHS drugs bill. Surely the government should be promoting research into natural (and cheaper) ways of combatting Parkinson’s? It could save a lot of money, as well as improve the lives of hundreds of thousands of sufferers and their families.

I did find some exceptions to the drug-oriented research, but none in the UK. One was Mark Mattson in the United States, who referred me to a patient collaborator—Bill Curtis—who has suffered from Parkinson’s for a quarter of a century. Through a Zoom discussion with Bill, I was greatly encouraged. Although he was using drugs to manage symptoms, he was also using natural methods that were enabling him to live a near-normal life. Another exception was the ExpoBiome project at the University of Luxembourg, funded by the European Research Council. At the time of writing this blog, they have not yet reported on their results, so I will comment on their project at a later date. In 2025, I came across a third – Matt Phillips in New Zealand – a doctor and researcher, whose research was focused on natural ways of combatting Parkinson’s.

What is Parkinson’s Disease?

Before going into the details of my research, and the personal strategy I developed, it may be useful to provide a summary of Parkinson’s Disease, because it is far more complex than most people think. Parkinson’s has no cure and it is progressive—i.e. it gets worse over time. Whilst the most obvious symptom is often a tremor—typically starting on one side—Parkinson’s also involves a wide range of motor and non-motor symptoms.

Motor symptoms can include muscular rigidity, slowness of movement, and balance problems. Early signs can be subtle: a slight tremor in one hand or leg, difficulty turning over in bed, reduced facial expression, diminished arm swing, a stooped posture, or a change in handwriting (which often becomes smaller and more cramped as the sentence progresses).

As the disease advances, movement becomes more difficult. Walking may involve a shuffling gait, and some people experience episodes of “freezing”, where their feet feel temporarily glued to the floor. Speech may become softer or more monotone, swallowing can become more difficult, and involuntary muscle contractions may appear, particularly in the feet or hands. In more advanced stages, some individuals may have to rely on a mobility scooter or may even become bedbound within as short a period as a decade of onset.

Non-motor symptoms can emerge years before diagnosis and tend to accumulate as the condition progresses. These may include constipation, REM sleep behaviour disorder (in which people physically act out dreams), fatigue, loss of smell , and mood changes such as depression or anxiety. Urinary urgency, sometimes progressing to incontinence, and drops in blood pressure on standing are also common.

Other symptoms can include excessive sweating, drooling, and sexual dysfunction. Cognitive changes often develop gradually: slowed thinking, difficulty concentrating, memory issues, hallucinations, and trouble with planning or multitasking. Later on, some people may develop Parkinson’s-related dementia. There can also be apathy, impulse control disorders (such as compulsive gambling or shopping), and a general loss of motivation or emotional responsiveness.

These non-motor symptoms may be less visible than tremor or stiffness, but they can be among the most disruptive, deeply affecting both the person with Parkinson’s and those close to them.

Why did I decline drugs?

There are two main reasons for me declining drugs, at this early stage of the disease. Firstly, all drugs have benefits and side effects—even commonly used pain relievers such as aspirin or ibuprofen. Therefore, when deciding whether to take a drug, one needs to weigh up the pros and cons. For example, aspirin can be life-saving for some because it reduces the risk of heart attacks and strokes in those with a history of cardiovascular problems. But it also carries risks because it can cause stomach ulcers, internal bleeding, and other complications. So, for people who have had heart attacks the benefits might outweigh the risks. But for those who have healthy hearts, the risks may not be worth it.

Parkinson’s medication poses a similar dilemma. While the drugs can offer symptom relief, they also come with side effects and long-term considerations. Some are known, such as the possibility of diminishing returns or complications such as dyskinesia—i.e. involuntary, erratic, writhing movements. More worringly, the medications can in some cases promote addictions – e.g. to sex or gambling – and there are tragic examples of sufferers’ relationships or finances being devestated as a result. Other effects may be unknown and may only become recognised with funded research studies and the long term accumulation of data. I’m not ruling drugs out forever—I may well need them in the future—but for the moment my symptoms such as tremor and stiffness are manageable. At the moment, the benefits of taking drugs do not outweigh the known and potential side effects.

The second reason is that my academic discipline—analytical psychology—has taught me to be wary of an overly-dominant paradigm that introduces a one-sided approach. That is, although there is much benefit from a biomedical paradigm that produces many life-saving drugs, it can become one-sided when drugs become the first and only port of call. This may not produce the best outcome for patients, and could inflate NHS costs unnecessarily. Drugs need to be viewed as one—sometimes necessary—component in an overall treatment approach, not as the only approach.

My research approach

As I started to look at research into Parkinson’s, I discovered that my consultant was correct in saying that drugs don’t slow progress, they only moderate the symptoms. So, even with drugs, Parkinson’s symptoms will get worse over time—requiring more drugs to moderate them, and eventually going beyond the point when the drugs are effective. Exercise is the only scientifically proven way to slow down the progress of the disease.

However, ‘scientific proof’ is an incredibly high standard to reach, and there may be beneficial approaches that haven’t been researched yet with humans. So, I looked at the research there was—mainly with animals—and asked three questions:

- Is there evidence that this approach could be of benefit to me?

- Is there evidence that this approach might do me harm?

- Is this approach something I can sustain?

Whenever I was able to answer the questions yes-no-yes then I included the approach in my personal strategy. That is, I included it when there was evidence it could be of benefit, wouldn’t do me harm, and is something I can sustain. It is a living strategy, i.e. one that I develop as I learn more about the disease.

My personal strategy

After reading various research reports, this strategy has been adopted on the assumption that, in early Parkinson’s, promoting things like ‘good’ autophagy, mitochondrial function, neuroplasticity, and GDNF are likely to slow progress. I don’t understand what all these terms mean, particularly GDNF, though I do understand there is an outside chance GDNF might help dopamine-producing cells in the substantia nigra regenerate, albeit at a very slow rate. Though, this may only refer to reviving damaged cells—there is no evidence yet that it might replace dead cells.

From my non-medical perspective, my understanding of the likely effectiveness of the various natural ways of promoting autophagy, etc., is as follows (1=weakest, 5=strongest):

5 Exercise. There is a need to include some aerobic exercise or HIIT, stimulating heart rate of 80%-90% of maximum heart rate, which for me is 220-65=155. I.e. my heart rate needs to achieve 124 to 140.

4 Strict intermittent fasting, drinking only water, black coffee, or black tea. Autophagy might start anywhere between 12 to 24 hours after the start of the fast (the timing is a guess from animal studies, because the lack of research with people means the timing is unknown in humans).

3 A ketogenic diet and/or a polyphenol rich diet, omega-3 fats, and fermented foods.

2 Cold exposure, optimised sleep, low stress levels, cognitive stimulation, antioxidants, fibre.

1 Natural level of autophagy, etc., which declines with age.

Aims

The aim of my strategy is to:

- slow progress of the disease as much as possible;

- delay the start of medications as long as possible;

- be in the best possible state when new medications might stop the progress of Parkinson’s (best guess from current research is mid 2030s); and

- undertake a regime that is sustainable because it is not too onerous.

Strategy

Exercise

Play golf three times per week.

High Intensity Interval Training (HIIT) on a cycle machine. I originally aimed for three half hour sessions per week but this is too much for me. Also, Matt Phillips (and others) suggest exercise needs to follow the principle of ‘hormesis’ – that is, balance the stress on the body with an adequate time of recovery. More exercise is not necessarily better, only exercise that promotes neuroplasticity.

To make this exercise more engaging, I have started using Virtual Reality (Quest 3S & the VZfit app), which has increased time and motivation on the cycle machine. I cycle on routes in various places around the world, led by a trainer, all in my home-office. Here is a 30-second video that shows what this looks like:

Resistance exercise on a rowing machine, when watching TV, typically twice a week.

Table tennis once a week.

There is a good talk on the best types of exercise at https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=Q6d0J81VomY

Intermittent Fasting

From mid-December to mid-April, 16:8 (loosely adhered to).

Mid-April onwards, two 35 hour fasts per week, strictly adhered to, on non-exercise days. This is usually Monday evening to Wednesday morning, and Thursday evening to Saturday morning. Water (with a small amount of electrolytes added) and black coffee. Tea made me hungry! This was surprisingly easy to stick to—there were occasionally little hunger pangs, but they quickly go away.

Initially, I ate normally on other days. From July 2025, I modified this to follow a ‘hormesis’ rotation between fasting, carbohydate, and ketogenic days. The order was tweaked in August, which means my weekly regime tends to be:

- Monday – carb (golf and table tennis)

- Tuesday – keto (rowing)

- Wednesday – fast (rest)

- Thursday – carb (golf, optionally HIIT on cycle machine)

- Friday – keto (HIIT on cycle machine or rest)

- Saturday – keto (golf and rowing)

- Sunday – fast (rest)

I sometimes refer to the carb days as ‘chocolate days’. Dark chocolate may offer people with Parkinson’s modest benefits through mood and dopamine support, mild stimulation, and antioxidant effects. To be eaten in moderation, of course (I sometimes forget that bit!).

Diet

On non-fasting days, breakfast is muesli, ground ginger, berries, nuts, and kefir.

Supplements (non-fasting days):

- Vitamin D – 1,000iu

- CO Enzyme Q10 – 300mg

- Cod Liver Oil

- NAC – 600mg

- Ursolic acid – 75mg, will increase to 300mg

- 50+ multivitamins (not every day, to avoid excess, esp. vitamin A)

- Pomegranate and cranberry tablets (or drinks).

Supplements (fasting days):

- Multivitamins

- Electrolyes (fast/keto friendly capsules)

Sleep

Aim for average eight hours (difficult on second night of fast).

Use Fitbit to monitor.

Use Fitbit ‘premium’ meditations to induce good sleep.

Stress management

As stress can accelerate the progress of Parkinson’s, I’ve stopped (most) commercial and academic work (i.e. semi-retired), only continuing things I find enjoyable.

Minimised contact in stressful relationships.

Now doing things I mainly enjoy, at a pace I find comfortable.

Social connections

Golf provides a lot of social contact.

Maintaining some existing social connections where not likely to induce stress.

Cognitive stimulation

Continuing academic research and writing where enjoyable.

Golf provides some problem-solving skills (and have occasional lessons).

Chess problem solving app is a hobby.

Methods not used

There are two popular ways of combatting Parkinson’s that I’m not currently using:

- Red light therapy. I’m not sure about the risks. My mother developed dry macular degeneration in her later years and became almost fully blind. Red light therapy does not currently pass my test of ‘could it do me harm?’ I would therefore only use red light therapy under medical supervision, and backed by clear research that demonstrated no risk of macular degeneration.

- Beechband. This wrist device, which is based on research that regular tapping can reduce symptoms, is both of potential benefit and – as far as one can tell – safe. However, it has a very short battery life (2-3 hours) and then requires 45min to recharge. This doesn’t fit with my lifestyle because, if I am out for between 8 to 12 hours, I would have to carry several devices and then charge them all when I got home. This is impractical. Therefore, this device doesn’t pass my test of ‘is it sustainable?’ Hopefully, they will develop a version that uses replaceable, rechargeable AAA batteries that can be replaced in a few seconds. Then I could charge up a batch and take them with me for the day. This would make the device cheaper and provide a continuous signal.

Impact of strategy

The strategy has had a positive impact on my symptoms. I had lost some dexterity in my fingers which meant, for example, that I couldn’t throw things at all well—but that dexterity has now returned. Another symptom that has gone is a clumsiness when getting dressed. My balance has improved, though not back to 100%. The stiffness on one side has improved, as has the tremor in my leg—which remains the most prominent symptom. I used to play drums and had lost the rhythm in my right foot, which has partly returned but is still not good enough to drum. And there are other improvements.

However, the improvements seem to have reached a plateau. I presume this is because the cells that are still alive have reached a peak of efficiency, but the dead cells have not been revived. I am continuing the strategy in the hope that it will prevent or slow further deterioration, and possibly even start to replace the dead cells (though, I haven’t seen any evidence to date that suggests that can happen). Some symptoms—such as occasional memory lapses—seem unchanged, though it is difficult to separate out the effects of Parkinson’s from normal deterioration that comes with age.

Other observations

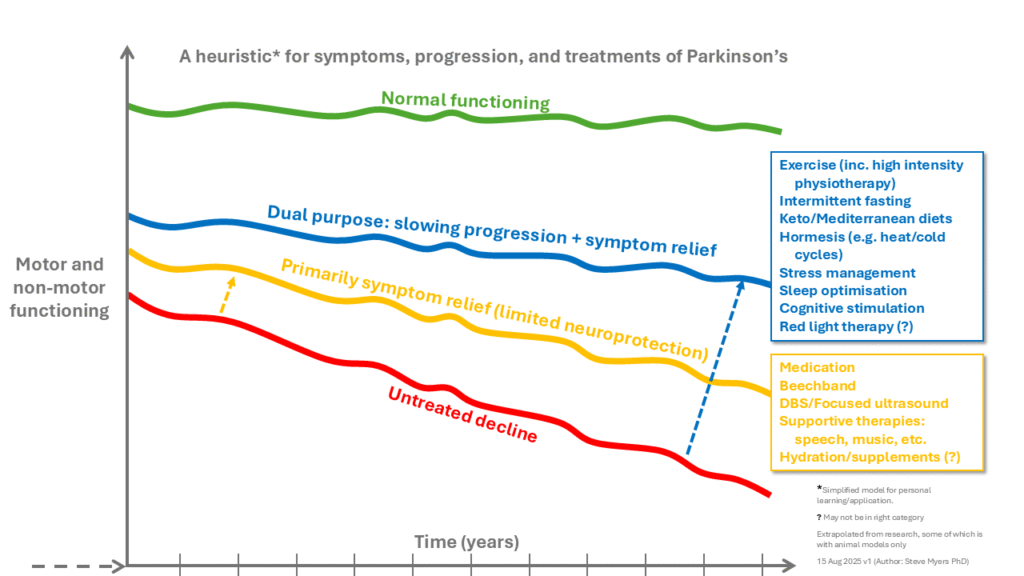

The following diagram is a heuristic to summarise how I see the various approaches to Parkinson’s working. As a heuristic, it is an oversimplification. For example, the lines can all start at different places, and there should be many more lines, with different origins and slopes, for each intervention and each symptom. The diagram doesn’t provide any detail because it varies for each individual, and detail would imply a level of accuracy that isn’t warranted. The underlying reality is very complex, but the diagram is kept simple for heuristic reasons (i.e understanding, learning, prompting thought or discussion).

One other important thing to note is that Parknson’s is sometimes confused in the initial stages with the much more serious condition of PSP (Progressive Supranuclear Palsy) in which decline is much more rapid. Differentiating Parkinson’s from PSP is difficult, even for the neurologist, but clues that you might have it include:

- Early and prominent backward falls.

- A fixed gaze.

- Symmetrical rigidity.

- Difficulty looking up or (especially) down without moving your head.

- Minimal or no response to levodopa (which can happen initially with PD but the neurologist can recognise/interpret over time).

If you have any of these symptoms, then discuss them with your Parkinson’s consultant urgently.

Conclusions

This strategy is a single-person, self-experiment. The results so far have been encouraging: some symptoms have lessened or stabilised. Nevertheless, Parkinson’s is a complex and progressive condition with many unknowns, and I cannot be certain that this approach will continue to work in the long term. Nor can I assume that what works for me will necessarily benefit others in the same way. That said, there is a strong case for greater investment in natural, non-pharmaceutical interventions—rather than letting research be driven largely by commercial interests and a biomedical paradigm. People with Parkinson’s deserve more than a one-size-fits-all model of care.

If you are considering trying any of the strategies outlined above, you must do so at your own discretion and risk. Where there is uncertainty, it is always wise to consult with a medical professional first.

Further information

There is a video by Dr Matthew Phillips, on why intermittent fasting helps moderate the symptoms of Parkinson’s Disease, at https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=uVXPcv9qYr8

Matt Phillips has a second video that takes a more overall look at strategies for combatting Parkinson’s. In the ‘iceberg’ model he presents, drugs at the top only moderates symptoms. It is the hormesis at the lower levels that have the potential to slow progress (as well as moderate symptoms). This second video is at: https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=3uSKVmYNui8