This blog article is an in-depth analysis of a major research report into the effect of intermittent fasting (IF) on Parkinson’s disease (PD) in humans. It was funded by the European Research Council (ERC) and carried out by the ExpoBiome project at the University of Luxembourg. The report is a pre‑print (i.e. not yet peer‑reviewed) and is published on an academic website dedicated to pre‑prints.

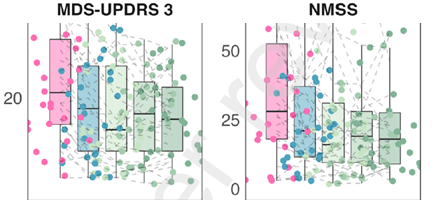

In summary, the research suggests that IF significantly reduces both motor and non‑motor symptoms, and that this improvement is sustained over a long period. This is demonstrated by two graphs showing the range of motor and non‑motor symptoms before the study (pink column), after one week of ‘prolonged fasting’ (blue), and then at three reviews over the next 12 months (green), during which the participants used ‘time‑restricted eating’ (TRE).

The graphs show a significant drop in symptoms after the week-long prolonged fast, and then remained broadly stable over the next 12 months with time‑restricted eating. This last finding is particularly striking because it appears to suggest (though, not claimed by the authors) that IF not only reduces symptoms but might also slow progression of the disease.

However, having read the detail of the report, the research is not as robust as I would have liked. The study was designed to be exploratory – so, by its own admission in the planning phase, it didn’t meet the gold standard of research. Nevertheless, although it is plausible that these scores are due to IF, there are several confounding factors which have not been adequately eliminated. It is also plausible, therefore, that the results are due to these other factors and not to IF.

A further concern is that the report does not seem to recognise its limitations. The presence of several confounding factors suggests that further research is needed before firm conclusions can be drawn. However, the research report does draw such conclusions, e.g. by saying “prolonged fasting followed by time-restricted eating has a sustained beneficial effect in patients with PD”. For me the claim goes too far for a research report. Although my personal experience and reading of other research suggests that claim is likely true, there are too many confounding factors that have not been adequately addressed or, in some cases, not even identified to put in a peer-reviewed submission for publication.

In this article, I examine the findings, outline my concerns, and draw some conclusions about the robustness of the report. In summary, having waited for a long time for these results, I feel a strong sense of disappointment.

Findings

There were 31 participants in the study, most of whom had early‑stage Parkinson’s disease and were on medication. The protocol involved one week of medically supervised prolonged fasting – around 350 calories per day – followed by 12 months of 16:8 time‑restricted eating. The 16:8 protocol typically involves fasting overnight, for example from 6pm to 10am the following day, and eating within the remaining eight‑hour window.

The study found that, after the one‑week prolonged fast, there was a statistically significant improvement in both clinician‑rated motor symptoms (UPDRS Part III) and non‑motor symptoms (NMSS). There were also modest improvements in mood measures, and reductions in BMI and systolic blood pressure. However, self‑reported experiences of daily living (UPDRS Part II), quality of life (PDQ‑39), and sleep measures did not show significant improvement.

Over the following 12 months, symptoms remained stable or even reduced slightly. But there were also changes that were tracked by the project but not introduced by it. Participants’ diets shifted towards a more plant‑based, Mediterranean‑style pattern, and their independent clinicians increased levodopa medication levels (LEDD) significantly over the course of the year.

Based on these results, the research team concluded that IF was beneficial to people with PD as a result of “enhanced ketogenesis, increased autophagy, decreases of mTOR, IGF‑1 and overall reduced inflammation as well as a modulated gut microbiome acting directly or indirectly, and a potentially re‑established serotonin–dopamine balance”. In their view, “fasting interventions may provide an additional dimension in PD care, leading not only to improvements in non‑motor, but also in motor symptoms”.

These findings are interesting and potentially very important. However, there are several confounding factors in this study that undermine both the reported conclusions and an inference (discussed below) that can be drawn from the long-term data. These criticisms do not necessarily invalidate the conclusions, but they do suggest that more detailed analysis and stronger argument is needed before full publication.

Confounding factors and unresolved questions

Some limitations of the study are acknowledged in the original project design and/or by the authors of the research report. But some of these limitations and others are not fully addressed in the report.

Open-label design

One important issue concerns the medical assessment of UPDRS Part III, one of the scales that improved. The assessment appears to have been conducted by members of the project team. That opens the door to unconscious bias – i.e., a desire for the project to succeed may subtly influence how improvements are perceived or scored. In more robust studies this risk is eliminated by using independent assessors who are not involved in the intervention and who do not know the state of the research when the assessments take place. This ‘blind assessment’ was not the case in this research, which the original design recognised by describing the project as “open-label”.

Another feature of the open-label design is that participants also knew that they were taking part in an IF study. This introduces the possibility of response bias – i.e., during assessment, participants may unconsciously perform in ways they believe the medical assessors expect. In stronger study designs this is addressed by including a comparison group and by ensuring that participants are not aware of whether they are receiving the intervention being tested. For example, the study could have been described as consisting of dietary interventions, and the control group given a different diet to IF. This ‘blind participation’ did not happen in the ExpoBiome study, despite the fact that the original project design described it as a “controlled” study.

If this had been a gold standard study – consisting of both assessment and participant blindness – it would be ‘double-blind’. As an exploratory study, this is not a major problem, so long as the lack of double-blindness is mitigated as far as possible, and other confounding factors are minimised. However, the research report is not convincing on either of these.

Statistical analysis

A separate concern is that, during the 12‑month follow‑up period, medication doses were increased – presumably by participants’ own consultants who are independent of the project, although the report does not make this intervention entirely clear. This suggests that stable symptoms or slight improvements could potentially be explained by increased medication rather than fasting. The report tries to address this, using statistics which show that only the duration of the overnight fast and not LEDD (levodopa dose) had a significant impact on motor improvements.

However, their analysis appears to be based on a standard mixed effect model. Although this is a sophisticated analysis, this type of model does not allow for two-way interaction between medication and symptoms. But the relationship between these variables is dynamic or two-way – that is, if your symptoms change, then your consultant is likely to change the level of medication, but the level of medication can then change your symptoms.

I’ve no doubt that those involved in the project realise how medication and symptoms can influence each other. My difficulty is that the statistical analysis does not incorporate this two-way relationship between medication and symptom levels, and the report does not acknowledge or examine how that level of interaction affects the conclusions. This is not an esoteric statistical argument; it raises a serious question over the assertion that medication did not have a significant impact on symptoms.

Mismatch between clinician‑rated and self‑reported outcomes

A further concern is the mismatch between clinician‑rated improvements in scores and the absence of corresponding improvements in patients’ self‑reported daily functioning or quality of life. As indicated above, one possible interpretation is that the medical assessors were unconsciously biased towards improvement. But there are other potential explanations.

One alternative might be due to self-assessment and medical assessment looking at different things. In Parkinson’s disease, reductions in bradykinesia or rigidity can occur alongside increased dyskinesia, motor fluctuations, or loss of fine control – particularly when medications are used. In such cases, observable performance of certain symptoms may improve, whilst the person’s experience of daily functioning does not – because other medication-related symptoms might increase.

It is not possible to analyse this question further, because UPDRS Part III results are reported only as a total score rather than at item level (for example, rigidity versus bradykinesia versus gait). Without that detail, it is difficult to examine the reasons for this mismatch of self- and medical-assessment any further.

Medication masking of symptoms

Medication can mask symptoms, which makes UPDRS III assessments difficult to compare, for two reasons. For participants who were on medication (28 out of 31), if they were taking medication at the time of assessment, it is not clear whether the clinical assessments were conducted during on or off states. Also, for a true assessment of Parkinson’s symptoms, participants would ideally cease from taking medications for a period before the assessment, so that the unmedicated Parkinson’s baseline could be assessed. The report does not discuss how the assessments were carried out or under what conditions. This is another way in which medications may have influenced symptoms without being detected by statistical analysis.

Long-term stability

The 12-month results also invite a further inference, although the project team do not explicitly make it. At first glance, sustained improvement in UPDRS Part III over 12 months is striking. PD is a progressive disease and, although individuals may have stable periods, in a group of 31 people one would normally expect some deterioration amongst some participants over a year, thereby increasing average symptom scores. A stable or slightly lower group average therefore appears to suggest that IF might not only reduce symptoms but slow progression.

However, although this data may indicate something of genuine interest – i.e. a slowing of progression – it might also reflect some of the above factors that mask the continuation of progression, such as the interactive cycle between medication levels and symptoms. What concerns me is that the report included the data, left the reader to interpret its meaning, but did not identify or resolve the many questions that the data raised.

Other factors

Another compounding factor is the general improvement associated with fasting – well established in other research – that had the indirect effect of reducing symptoms without any underlying change in the expression of Parkinson’s or the underlying disease progression. For example, IF may have led to a reduction in the level of sugar consumption – and it was the lower sugar intake that produced the improvement in symptoms.

Another factor is that the initial week-long fast started with a bowel cleanse. What this involved is not explained, but it raises the question as to whether the initial improvements were due to the bowel cleanse rather than the fast itself. That is, the bowel cleanse may have affected the gut microbiome in a profound way, which in turn affected PD symptoms. This possibility is not recognised or discussed in the report.

I am also concerned by the fact that several of the measurement scales used were modified in some way so they are different to the standard usage. Most scales used in research have been through some form of validation and reliability procedure to ensure they consistently measure what they claim (or rather, the degree of reliability is established). If one removes items from scales, it can alter both the degree of validation and the reliability, which again can undermine the reliance one puts on the results.

Another factor is that, with only 31 participants, it is possible that the results might have reflected natural statistical variation. That is, the group happened, by chance, to include people whose symptoms did not progress during that year. Although statistical analysis tries to minimise that possibility, statements such as “p<.05” do not provide a guarantee that the results were not due to natural statistical variation; it only means that these results might be expected due to chance in one study out of every 20. Larger numbers of participants reduce this likelihood considerably.

There are also some inconsistencies that need further explanation. Although the modelling suggested a significant change in NMSS, it also said that “No factor was significant after FDR correction for any of the primary health outcomes.” What does this mean? Is it suggesting that the analysis of independent variables is misdirected, and one has to look at holistic effects? There is no discussion of this issue, which could be quite important.

Conclusions and next steps

This is potentially a seminal and significant piece of research – the first time that intermittent fasting has been given serious research attention in a human study. But there are multiple concerns, which include:

- Lack of control group

- Open-label design (assessor and participant)

- Expectancy and performance bias

- Medication escalation as a confounder

- Inability of standard mixed-effects models to handle feedback loops

- Clinician-rated vs self-reported divergence

- Possible masking of progression by medications

- General benefits due to factors other than IF per se

- Small-n statistical fragility

- Possible over-interpretation of sustained stability (implied not stated)

- Gap between exploratory design and strength of claims

Personally, I had been looking for a more measured and robust argument in the report, especially as this was an ERC-funded project from a prestigious organisation and team. Perhaps my expectations should have been tempered by the fact that the project’s original design suggests its primary focus is the gut microbiome rather than IF per se, so this paper may best be seen as a spin‑off rather than a definitive statement. In that context, it has highlighted potentially important effects of IF that are certainly worth further investigation. So, my disappointment reflects not the quality of the work itself, but the gap between my expectations and the tangential and exploratory nature of this study to the ExpoBiome project’s central work.

My own experience is that, as part of a broader holistic strategy including hormesis, exercise, diet, and other factors, intermittent fasting can contribute to a reduction in symptoms and possibly a slowing of progression. That experience is supported by the ExpoBiome findings, but not in a strong way. Just as my own findings might be confounded by subjective factors, the ExpoBiome findings may be confounded by other factors that it has not studied.

The bottom line is that this study is interesting as a first step. But first steps matter most when they are placed carefully. At present, this paper opens the door to important questions – but for me leaves too many of them unanswered.