The title of this blog highlights a hidden cost of Fred Olsen’s proposed wind farm that is in danger of receiving no attention: the mental-health impact of industrialising one of the nation’s most restorative landscapes. The debate around wind turbines nationally usually turns on carbon, grid capacity, energy costs or planning law. In the case of Fred Olsen’s industrial-scale wind farm on Hope Moor, the developer will also examine the trade-offs with ecological and environmental concerns — for example, arguing they are outweighed by the efficiency of 200m turbines.

But in the case of the proposal for a wind farm on the edge of the Yorkshire Dales, there is another important factor that we must not overlook — the nation’s mental health. There is mounting evidence from research that unspoilt natural landscapes support the nation’s mental health. When a proposal threatens to fundamentally alter one of those landscapes, the consequences are more than aesthetic. The UK is already in a mental-health crisis, and the Fred Olsen wind farm would push us further in that direction. And this mental-health dimension is almost always overlooked.

The Yorkshire Dales and the North Pennines are not simply regional beauty spots. They form part of Britain’s national psychological inheritance — landscapes that millions of people visit — but even those who don’t still draw comfort from knowing they remain unspoilt. Damaging them is therefore a national issue, not a local one. With mental-health problems costing the UK economy an estimated £117 billion a year, protecting the landscapes that demonstrably support resilience is not merely desirable — it is economically rational.

NATURE AND MENTAL HEALTH: THE EVIDENCE

A large body of research shows that spending time in natural environments — moorland, upland, woodland, rivers, and open countryside (e.g. Figure 1) — improves both physical and mental health. Systematic reviews over the past decade have found consistent associations with lower stress, reduced depression and anxiety, better mood, improved resilience, and even lower all‑cause mortality.

Figure 1: example of uplands/moorland in the Yorkshire Dales (photo © Yorkshire Dales National Park Authority)

These benefits depend on the landscape remaining natural, tranquil, and largely undisturbed. The NHS’s own “green social prescribing” programme rests on the fact that regular contact with nature reduces stress hormones, improves sleep, lowers blood pressure, and enhances wellbeing. This is not speculative. It is now an accepted part of public‑health strategy.

SCENIC QUALITY MATTERS — NOT JUST “GREEN SPACE”

Crucially, it is not only the presence of nature that matters. It is the quality of the landscape. In upland landscapes, scenic quality depends heavily on the integrity of the visible skyline.

The London School of Economics and the University of Sussex conducted a series of “Mappiness” studies that showed people are significantly happier in natural environments than in urban ones — even after controlling for personal factors and weather.

A further study, “Happiness is Greater in More Scenic Locations”, showed that scenicness itself has an independent effect. High‑quality, unspoilt landscapes are not merely pleasant. They are psychologically protective. Research consistently shows that even a single hour spent in a scenic natural environment lowers stress hormones and improves mood for days afterwards — and these restorative effects are strongest in landscapes that remain visually undisturbed.

LANDSCAPE AS A PUBLIC GOOD

Academic research has identified the non‑material benefits we gain from landscapes: tranquillity, aesthetic pleasure, sense of place, identity, inspiration, recreation, and connection. These are consistently linked with better mental health, lower stress, and greater life satisfaction.

This is why the UK protects areas like the Yorkshire Dales and the North Pennines. They are assets — not just ecologically, but psychologically. Once degraded, those benefits do not simply relocate somewhere else. They are lost because distinctive landscapes are not interchangeable.

Both the Yorkshire Dales National Park Authority and the North Pennines National Landscape have repeatedly warned of the cumulative harm caused by the industrialisation of upland fringes and moorland edges.

THE VISUAL INTRUSION OF A 200-METRE INDUSTRIAL SITE

The Hope Moor proposal would introduce twenty 200‑metre industrial structures into a currently undeveloped upland environment. These turbines would be visible across the Dales, across the Pennines, and across numerous protected viewpoints.

For residents and visitors, the intrusion is not trivial. Studies of wind turbines consistently find several negative effects. These are not speculative risks; they are consistently observed across multiple studies in comparable environments:

- increased annoyance and irritation

- deterioration in sleep

- reduced quality of life

- increased stress

- higher sensitivity to noise when turbines are visually dominant

Chronic annoyance, sleep disruption and landscape-related stress are well recognised contributors to poorer mental health. And these effects are strongest when turbines overpower the landscape’s existing character — exactly the situation at Hope Moor.

LOSS OF TRANQUILLITY, IDENTITY AND PLACE

The Yorkshire Dales and the North Pennines hold powerful cultural meaning, built up over centuries in art, literature, farming, walking, and tourism. They are landscapes that define national identity, most famously immortalised by the likes of James Herriott (All Creatures Great and Small) and JMW Turner.

Turner painted many vistas in and around the Yorkshire Dales. In the work below (Figure 2), the view from the north east of Richmond (Yorkshire) would be interrupted by the 200m turbines on the horizon to the right of the painting.

Figure 2: Richmond from the North East

The vistas Turner captured are not just artistic subjects; they represent a cultural continuity between past and present. When that skyline breaks, the link between the landscape and our shared sense of place breaks with it. If Fred Olsen replaces the open‑moor skyline with offshore‑scale machinery, then the psychological experience changes. Many vistas in and around the Yorkshire Dales no longer depict nature and tranquillity. The sense of immersion in natural space is interrupted. This is precisely the kind of shift environmental psychologists identify as reducing the restorative value of natural settings. The restorative quality that research consistently identifies begins to erode.

This is not a minor side‑effect. It is a transformation of the region’s psychological environment. If this proposal proceeds, Fred Olsen will not only be associated with renewable energy. It will also be remembered as the company that placed 200-metre industrial structures across one of Britain’s most restorative landscapes. That reputational association with the industrialisation of a nationally valued landscape would be permanent.

WHO BEARS THE COST?

The proposed turbines will impact the mental health not only of residents living near the site — who may experience chronic noise disturbance affecting sleep patterns — but also visitors to the Yorkshire Dales who are seeking escape, calm, or inspiration in an unspoilt, natural environment. Whether they are walkers, cyclists, or even touring by car, they will lose one of the most culturally significant and accessible large-scale open vistas in England. The nation will lose part of a cultural landscape that supports wellbeing and identity. Once lost here, similar landscapes nationwide become more vulnerable to comparable encroachment.

These costs are long‑term and irreversible. Once a landscape is industrialised, it is rarely restored. These landscapes also support a major tourism economy, drawing visitors precisely because of their tranquillity and scenic integrity. Once an upland skyline is industrialised, that draw is permanently diminished. No company can ignore the reputational implications of altering a nationally significant tourism asset.

Also, if 200-metre turbines can be placed here, on the edge of the Dales, then in practice there is no meaningful limit to where they might be placed next. If Hope Moor falls, every upland fringe in England becomes vulnerable to the same logic. Hope Moor would become a precedent with nationwide consequences.

THE REAL QUESTION

The government has repeatedly stressed the importance of improving the nation’s mental health. It is difficult to reconcile that priority with industrial proposals that erode the very landscapes known to support psychological resilience. If we genuinely value mental health — as the government, the NHS, and every major public‑health body claims — then proposals like Hope Moor cannot be assessed only through the lens of energy generation.

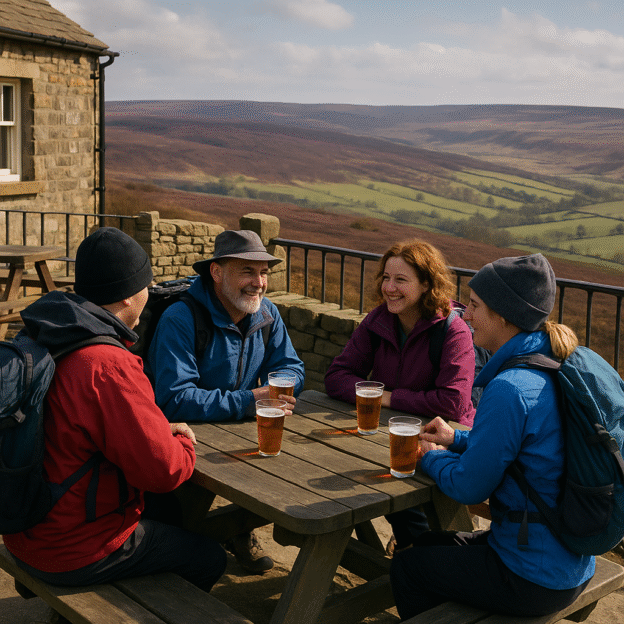

Figure 3: Group of walkers in North Yorkshire. Image used under fair dealing for the purposes of commentary or review.

Given these mental-health implications, this proposal warrants national rather than merely local scrutiny. But by ‘national’ I don’t mean that the decision should be taken by Westminster alone. What is at stake is not just a planning application, but the future of Britain’s restorative landscapes. The psychological health of the nation is not a luxury. It is part of national infrastructure. The landscapes that sustain that health are irreplaceable.

Fred Olsen still has the opportunity to show genuine leadership by withdrawing this proposal voluntarily, before substantial reputational harm is done. Protecting a landscape that supports the mental health of millions would speak far more strongly for the company’s values than pursuing a project that so clearly undermines them.

CONCLUSION

Fred Olsen’s proposed industrial-scale wind farm at Hope Moor is not simply a renewable‑energy project. It is a permanent industrial installation in one of England’s most psychologically valuable landscapes. The evidence is clear: natural, tranquil, scenic landscapes play a measurable role in supporting wellbeing. Damaging them is not a neutral act. It carries costs.

If we allow high‑scenic‑quality landscapes to be sacrificed, we do so at the expense of the nation’s mental health. Some landscapes belong to the nation — and to the visitors from around the world who come to experience them.