After being diagnosed with Parkinson’s disease (PD), I developed a personal anti-PD strategy to slow down its progression. One component of that plan was intermittent fasting (IF) for which, in recent years, there has been emerging research to suggest that it might help those with PD.

In this blog article, I offer my understanding of the current state of that research, and go through some of the provisional but practical ideas and principles that I’ve adopted in my fight with PD.

Important caveats

Before getting into the detail, please note that nothing in this article should be taken as medical advice. I am not a medic or biologist (although I do academic research, it is in a different discipline). What follows is simply my best guess about how intermittent fasting might help People with Parkinson’s (PwP) such as me. It is based on reading research reports, following the work of those who research IF and PD, and reflecting on my own experience of living with PD and the contribution that IF has made

Intermittent fasting isn’t suitable for everyone. It can be particularly risky for people with various conditions, including:

- Being underweight

- Having diabetes or blood-sugar instability

- A history of eating disorders

- Chronic kidney or liver disease

- Those who are pregnant or breastfeeding

- And other conditions of which I am not aware.

Also, I have no knowledge of the interaction of fasting with various drugs, including those used in treating Parkinson’s.

If you are a PwP, it is up to you to choose how to proceed, after making yourself aware of the potential benefits and risks to you personally, not all of which are identified in this article. My intention is not to promote a particular fasting regime but to extrapolate from the research and my experience to provide an informed guess as to the best options available.

What is intermittent fasting?

Intermittent fasting (IF) isn’t a diet in the traditional sense—it doesn’t prescribe what to eat, but rather when to eat. It involves cycling between periods of eating and not eating, giving the body extended breaks from food intake.

During fasting, levels of insulin and glucose drop, so the body switches from using sugar as its main energy source to burning fat and producing ketones. This metabolic shift triggers a number of processes such as autophagy—the clearing out of damaged cellular components—and changes in mitochondrial function, inflammation, and hormone regulation. No one knows how long it takes for a fast to start ramping up autophagy, etc., but the best guess is around 12 to 16 hours. And it gets more intense the longer the fast.

The effects of IF are thought to be various health benefits, so long as the conditions are right. For people with PwP, these mechanisms have prompted growing interest in whether fasting might help protect or stabilise vulnerable brain cells.

The simplest version of IF is known as time-restricted eating (TRE), where all meals are consumed within a set window—often eight hours—followed by a sixteen-hour fast, which usually includes overnight. This form of TRE is often written as 16:8. Other forms include alternate-day fasting and prolonged fasts, such as going 24–36 hours without food once or twice a week, or even longer. Personally, I’ve set the limit at 35 hours because anything longer would probably require close medical supervision.

There can also be different levels of fast. Some—particularly those over extended periods of time—limit calories to 400 or 500 per day. Other fasts are strict, involving no calories. They might allow water only, or perhaps black coffee or tea without sugar or sweeteners. To help avoid dehydration and fatigue, they might include fasting-compatible electrolytes.

What the research shows

Over the last quarter of a century, there have been several research projects into IF and PD, though they have almost exclusively been with animals (until 2025). Some of these are listed below.

The majority of research projects that I found suggested IF improved PD symptoms. However, some suggested no impact or—in one case—IF made PD worse.

| Year | Study | Model / Type | Main Finding |

| 1999 – positive | Duan & Mattson – J Neurosci Res | MPTP (rodent) | Eating less food and using a glucose-restricting compound helped protect dopamine-producing brain cells and improved movement in mice. |

| 2003 – no impact | Morgan et al. – J Gerontol A | MPTP (older mice) | Reducing food intake did not protect the brain’s movement cells in older mice. |

| 2004 – positive | Maswood et al. – PNAS | Primate | Monkeys on a reduced-calorie diet had higher levels of nerve-growth chemicals and fewer Parkinson-like problems. |

| 2005 – positive | Holmer et al. – Synapse | MPTP (mouse) | Fasting changed key brain chemicals involved in movement, hinting at how it might protect nerve cells. |

| 2008 – no impact | Armentero et al. – Exp Neurol | 6-OHDA (rat) | Eating less food did not prevent damage to dopamine-producing neurons in this Parkinson’s model. |

| 2018 – negative | Tatulli et al. – Front Cell Neurosci | Rotenone (mouse) | In this study, fasting actually made nerve-cell damage worse, showing it can be harmful in some conditions. |

| 2019 – positive | Zhou et al. – Neurotherapeutics | MPTP (mouse) | A “fasting-mimicking diet” helped mice move better and kept more brain cells alive, possibly by improving gut bacteria balance. |

| 2021 – positive | Neth et al. – Front Neurol | Review | Summarised animal research and early human evidence suggesting fasting may support brain-cell health, but data are still limited. |

| 2022 – positive | Wang et al. – Nutrients | Review | Reviewed possible ways fasting might help Parkinson’s—through better cell clean-up, reduced inflammation, and a healthier gut. |

| 2023 – positive | Ojha et al. – Neurotoxicology | MPTP (mouse) | Mice that fasted every other day lost fewer dopamine-producing neurons and moved more easily. |

| 2023 – positive | Hansen et al. – BMJ Open (ExpoBiome Protocol) | Human protocol | Describes (before starting) a human trial examining how fasting affects gut bacteria and immune balance in Parkinson’s. |

| 2025 – positive | Szegő et al. – Nat Commun | rAAV-α-synuclein (mouse) | Regular fasting reduced build-up of Parkinson’s-related proteins and improved movement in mice. |

Animal research does not always translate directly into humans. One reason is that animals don’t develop PD. So, most studies involve doing IF first, then introducing a toxin to damage animal brain cells in a way that mimics PD, and seeing what happens (compared with a control group that did not do IF). However, the last two studies are particularly interesting because they used a different approach.

The 2025 rAAV study

This used a new technique that caused cell damage to develop and progress in the animals, and then it introduced IF (using an alternate-day fasting regime). This is much closer to what happens in people. The study was able to see what happened to both the level of symptoms and the rate of progression.

The researchers found that IF moderated symptoms and slowed disease progression by promoting autophagy (the process of clearing out damaged cells) and by suppressing neuroinflammation. The effect was weaker in older mice, but still present.

ExpoBiome Protocol

The 2023 plan was for a two-year study to report in 2025. It was sponsored by the European Union, with two strands to investigate the impact of IF on humans with PD or Rheumatoid Arthritis. It is the first major study with humans that is directly relevant to Parkinson’s because PwP were participants in the PD strand.

The study involved an initial week of prolonged fasting. It began with a colon cleanse and then participants were restricted to 400 calories per day. For the following year, patients switched to a lighter form of fasting – daily time-restricted eating (TRE) following the 16:8 pattern.

The Rheumatoid Arthritis strand

The results were reported in a preprint in July 2025. It showed that—whilst individuals vary—the proportion of RA patients with “high disease activity” dropped from 62% to 24% within the first week.

Over the following year, disease activity crept back up to 37%, but there were still sustained improvements in body mass index, blood pressure, and other biological markers.

The authors conclude: “Our data show the profound impacts of fasting and diet on RA … over time.” Their discussion also highlighted the importance of both meal timing and diet quality in driving benefits.

The PD strand

The results were presented at an international conference in September 2025. The results varied for different individuals but on average motor symptoms improved by 34% and non-motor symptoms improved by 36%.

The benefits lasted throughout the year with the TRE. This suggests that IF not only reduces symptoms but also slows or perhaps even stops progression.

Is this enough research?

No. For intermittent fasting to become a major form of treatment—for example recommended to the NHS in the UK by NICE (the National Institute for Health and Care Excellence)—much more research is needed, e.g. to confirm and reconfirm the benefits, look at the best kinds of IF, and produce guidelines on things like dos, don’ts, risks, interactions with drugs, etc.

My own experience

The dearth of research did not stop me from experimenting with IF in my personal anti-PD plan.

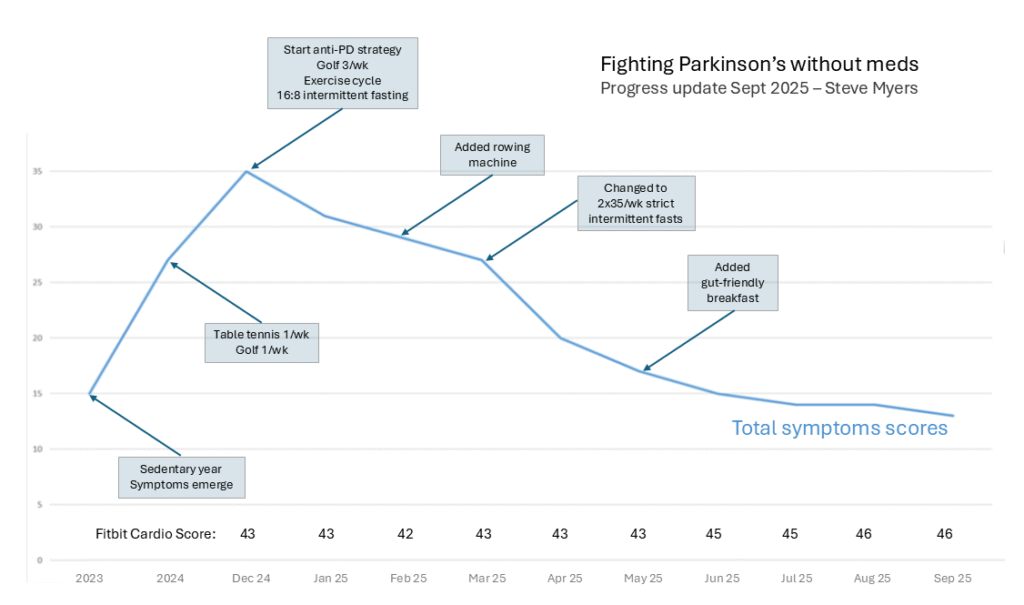

The impact on my symptoms is shown in the below graph. Each month, I score a range of symptoms and then produce a total score using an Excel spreadsheet.

Fasting has helped reduce my symptoms throughout 2025. At the time of writing (October 2025), I continue to fast, but the improvements seem to have reached a plateau.

Tentative interpretations

The paucity of research for IF and PD, combined with the fact that my expertise is neither in medicine nor biology, means that any conclusions I might draw are speculative and provisional.

With one notable exception (that I’ll examine shortly), most of the research and my personal experience tend to suggest that IF can help moderate PD symptoms and potentially slow progression.

Also, my experience alongside the ExpoBiome results seem to suggest that the more intensive the fast, the quicker the results:

- ExpoBiome achieved an average improvement of circa 35% after a week-long prolonged fast.

- My individual 2x35hr/wk regime produced a 40% improvement after four months.

- My 16:8 regime led to a 23% improvement after three months.

- The ExpoBiome follow-up fast—16:8 for a year—resulted in the improvements remaining stable.

- My own fasting regime has now reached a plateau.

However, the plateau suggests there is only a certain degree of improvement that can be achieved. My best guess is that IF cannot revive dead cells but it can improve the functioning of the surrounding cells.

Cautionary research

Although the most exciting research is the more recent rAAV and Expobiome work, I found myself particularly intrigued by one of the earlier studies—the one that produced a negative result. After looking at it, there were some differences in the method used that may provide helpful guidelines for the use of IF.

When animal studies did IF first, it acted as a kind of pre-conditioning. The animals’ brain cells were put under the right amount of stress and given time to build up defences, efficiency, and strength. The researchers then introduced the toxin.

However, the negative (rotenone) study applied fasting at the same time as the toxin. That combination effectively hit the brain with two energy stresses at once. In that situation, fasting added stress upon stress, which became too much. So, the fasting helped weaken the brain cells rather than strengthen them.

Hormesis

To me, the negative research result points to the principle of hormesis: a mild stress (whether fasting, exercise, dietary change, cold exposure, etc.) can be beneficial only if there is enough recovery afterwards. Without recovery, the system never adapts—it simply breaks down. I find that idea helpful in practice: if I’m ill, overtired, or recovering from something else, I postpone fasting rather than add another stress to the mix.

A similar principle appears in cancer research. When fasting is used before or between chemotherapy cycles, it can make healthy cells more resilient and help the body tolerate treatment, whilst leaving many cancer cells more vulnerable—a process called ‘differential stress resistance’. But in other cases, especially where tumours have adapted to use fats or ketones as fuel, fasting can have the opposite effect—weakening the person rather than the cancer.

Conclusions

Taken together, these research examples suggest that fasting is a powerful biological stressor, not a neutral act. It can activate deep repair mechanisms when the body is ready for them, but it can also expose hidden vulnerabilities if introduced at the wrong moment. For me, the lesson is to listen carefully to my body, start gently, and avoid fasting during illness, exhaustion, stress, or during significant changes. Used wisely, it might support resilience; used unwisely, it risks adding strain to an already challenged system.

IF is not a panacea or silver bullet, but it can potentially complement other treatments such as exercise, medications, devices (e.g. Beechband—a tremor-reducing wearable), good sleep hygiene, stress management, etc. Personally, at the time of writing, I use some of these (e.g. exercise, sleep hygiene), but don’t use others (e.g. meds, Beechband). Therefore, I have a partial but not comprehensive experience.

If any reader wishes to use IF, they do so at their own risk, and it may be sensible to discuss it first with their healthcare professional. Intermittent fasting can carry risks such as dehydration, dizziness, fatigue, or nutritional deficiencies and, in some situations, it can make serious illness worse (as in the cancer example).

In PwPs, fasting might also temporarily worsen symptoms such as stiffness, tremor, or low blood pressure, especially if medication timing or food intake is disrupted. I’ve experienced some of the temporary deterioration but it doesn’t seem to have detracted from the longer term improvements.

Post script – practical notes

In my regime, I introduced fasting gradually (16:8 first, then 2×35). For the longer fasts, I found I needed to stay hydrated, take fasting-compatible electrolytes, and stick to water and black coffee (tea makes me feel hungry). I also avoid sweetener, because just the taste of sweetness can interfere with the autophagy process. I break the fast with a light, gut-friendly breakfast (berries, nuts, muesli, ginger, and kefir, with no added sugar).

I’ve also found self-monitoring helpful. I track:

- My Parkinson’s symptoms using an Excel spreadsheet.

- Heart rate, HRV, and cardiac score using a Fitbit—which also guides me as to whether I need more exercise or more recovery time each day.

- A blood-pressure monitor.

- Urine test strips to check:

- ketones (the more the better),

- hydration (the ideal is in the middle of the specific gravity range), and

- possible urine infection (indicated by nitrites and leukocytes, though the results can apparently be unreliable for over-65s).

Keeping an eye on all these helps me stay within safe boundaries and notice early if fasting is tipping from helpful challenge to harmful stress.