To support Fred Olsen Renewables’ proposed wind farm in North Yorkshire, they have produced a website with images that make the turbines look as little as 30 metres high. However, buried in the detail it says the real ones would be 200 metres. Yet developers are required to make accurate images, to give communities an honest sense of scale and prominence.

Nothing on Fred Olsen Renewables’ Hope Moor webpage appears to meet those standards. Why has the company got their images so wrong — and why does it matter?

There are two possibilities. Either the Hope Moor images are inaccurate by accident or by design, but both possibilities raise serious concerns. If it is by accident, it raises questions about Fred Olsen Renewables’ competence. If they’re misleading by design, it raises questions about their integrity. This article investigates these two options in detail and evaluates the implications for democratic decision making.

The scale of Hope Moor Wind Farm

Fred Olsen Renewables’ outline proposal to the Secretary of State includes a map that shows the site is approximately 5km wide and 3km deep. Their website shows they are considering 20 turbines that are each 200m high.

To provide a fair representation of that height, Image 2 below includes the Deansgate Square South Tower which is 201m high. It is the tallest building in the picture, second skyscraper from the left. It has 64 floors and is the tallest building in the UK outside of London. It is the same height as the proposed turbines.

Image 2: Deansgate Square South Tower (201m, tallest building, second skyscraper from left)

Fred Olsen Renewables’ images

On the Hope Moor Wind Farm website, Fred Olsen Renewables use three main pictures. The first is the main banner which has moving images. Figure 3 is a snapshot from one of them:

Figure 3: Hope Moor banner image

We can get a sense of proportion from the road track and pixel counts in the image to work out the suggested height of the tower. The implied height depends on whether the road is single- or double-track.

If the road is single track (~4 metres wide), this suggests that the height of the tower (including the blade) is about 60 metres. If the road is double-track (~7 metres), this suggests the total height is about 100 metres.

Assuming the track is two-lane, as the Hope Moor turbines will be 200 metres, a more realistic proportion for the turbine would be as in Figure 4. I’ve also included the Angel of the North in the same proportions to help get a sense of the scale. If the road is a single track, the turbine would be 2/3rds higher again.

Figure 4 – Fred Olsen Renewables’ image corrected for proportions

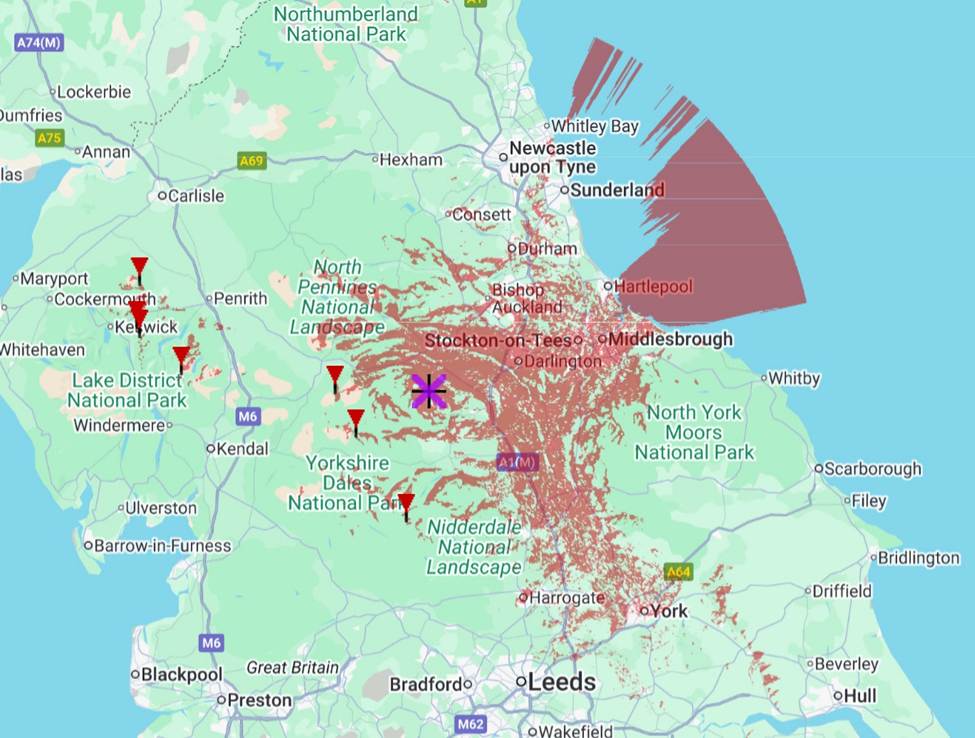

Another problem with the original Fred Olsen Renewables image is that it has a hilly landscape around it, implying that the turbines will likely be hidden behind hills. This is not the case for Hope Moor, which is a high, flat peak that can be seen across large swathes of the North East. This is illustrated by a Zone of Theoretical Visibility analysis – showing from where in the north the proposed wind farm will be visible:

Figure 5: Zone of Theoretical Visibility for Hope Moor Wind Farm

There are two other images of turbines used on Fred Olsen Renewables’ website for the proposed development – Figures 6 and 7 below. They foreground people and a road, making the turbines look between 30 and 40 metres high, which is a fraction of the height of the proposed turbines.

Figure 6 – Families foregrounding turbines

In this image above, Fred Olsen Renewables have included a person on stilts, which makes the turbines look even smaller.

Figure 7 – Road foregrounding turbines

In this image, it is impossible to say how far the turbines are behind the foregrounded road and heathers. Nevertheless, the impression is that the turbines are quite small by comparison with the Hope Moor Wind Farm turbines.

Why images matter

Images – which are a central concept in analytical psychology – carry tremendous power. In large-scale planning, images can shape public perception far more than any technical document. When visuals significantly understate the scale of a development, even in the early stages, they begin to soften objections, frame the discussion, persuade by generating ‘feelings’, and suppress opposition.

When visual material misrepresents scale, it doesn’t just distort perception — it distorts democracy. Public consultation depends on citizens having a clear sense of what is being proposed in their landscape. People can’t object to what they can’t visualise, and they can’t consent to what they’ve been shown only in miniature.

If the developer is challenged on these discrepancies, they may provide reassuring phrases such as ‘these are only early images’, or ‘they’re for illustration purposes only’, or ‘we haven’t entered the formal consultation stage yet’. But If the developer truly wanted to consult the community (rather than suppress valid concerns) it would not downplay the problem but be concerned by its error and correct its visuals immediately.

This project is already far enough advanced to have bypassed local councils and moved straight towards a single-decision process by the Secretary of State or their inspector. That means a great deal of planning, design, and PR work has already been done. If the company can invest in the level of lobbying and presentation that got it this far, it could just as easily have produced visuals that represent the scale honestly. To fail to do so is not a trivial oversight; it suggests either serious incompetence or intentional deception.

If it’s incompetence…

If the misleading images arise from simple error — from poor graphic design, lazy use of stock photos, or a failure to check proportions — then the implications are serious.

If a company can misjudge visual scale by that magnitude, what confidence can we have in its ability to manage something as complex as construction logistics, transport safety, or environmental impact assessment? Precision and accountability matter at all stages of the project.

And for major wind-farm applications, developers are required to produce verified photomontages — images constructed to standards that give communities an honest sense of scale and prominence. Nothing on Fred Olsen Renewables’ Hope Moor webpage appears to meet such standards (e.g. the Landscape Institute’s Technical Guidance Note 06/19).

If a company can fail to meet basic standards at the planning stage, what confidence can we have that they will be diligent at the construction and operation stages? What they do now demonstrates the attitudes, culture, and competence that they will draw on throughout the project.

If it’s intentional…

If, on the other hand, the imagery is deliberate — a calculated exercise in persuasion — then the issue shifts from competence to ethics. Developers’ PR teams understand the psychology of images. Every compositional choice can shape public mood:

- Foreground trickery: placing familiar objects such as roads, trees, or people close to the lens makes turbines seem small by comparison.

- Perspective compression: wide-angle lenses exaggerate distance, shrinking background structures.

- The human-warmth halo: bright colours, children, and sunny skies trigger feelings of community and wellbeing, subconsciously linking those emotions to the project itself.

- Selective framing: omitting access tracks, cables, and heavy machinery hides the industrial footprint.

Together, these techniques replace realism with reassurance — portraying an industrial development as something pastoral and benign. The use of children, families, and the man on stilts are all designed to create a feel-good factor. But that feeling is at odds with the sheer scale of the development, which is comparable to constructing 20 Deansgate Square South Towers on one of the most prominent flat peaks in the north. Such imagery does more than flatter to deceive. It subtly steers the consultation process, pre-empting opposition by giving communities a softened version of reality.

What it means for decision-making

Whether the misrepresentation is born of incompetence or intention, the effect is the same: it distorts the democratic and planning processes, undermines trust, and tilts the decision-making heavily in the developer’s and landowners’ favour. Public consultation relies on citizens having accurate information about what is being proposed in their landscape. When the very first images are deceptive, the entire process risks being built on illusion.

Ultimately, this isn’t only about turbines or technology; it’s about honesty in how the power of big organisations and land ownership presents itself. A company confident in its vision would have no need to make its turbines look smaller than they are.

Accuracy in public consultation is a matter of trust. Yet in this case, local councils have been bypassed, and the decision will rest with a single individual — the Secretary of State or their appointed inspector. That makes open, accurate public debate more important than ever. When the formal channels of representation are closed, the only remaining safeguard is an informed public.

If you believe that being honest about the scale of the proposed wind farm matters, please share this page.

Notes:

Figure 2: Deansgate Square Tower, Manchester by ChrisClarke88, licensed under CC BY-SA 4.0, via Wikimedia Commons (downloaded 12 November 2025).

All other images taken from hopemoor.co.uk and used under fair dealing principles. Some images have been cropped or had other images added for illustration purposes.