Ten years ago, there was a planning application for a single wind turbine that would have been closer to my home than the proposed Hope Moor Wind Farm. I remember seeing the notice on the lane and feeling a flicker of concern. But on reflection, I chose not to object. It was small-scale, sensitively placed, and part of what most of us would recognise as sensible progress towards renewables.

When I first heard of the Hope Moor proposal, I assumed it was something similar — akin to the spread of windmills in Holland between the 12th and 16th century. But the more I looked into the proposal, the more my concern deepened.

The True Scale of What’s Proposed

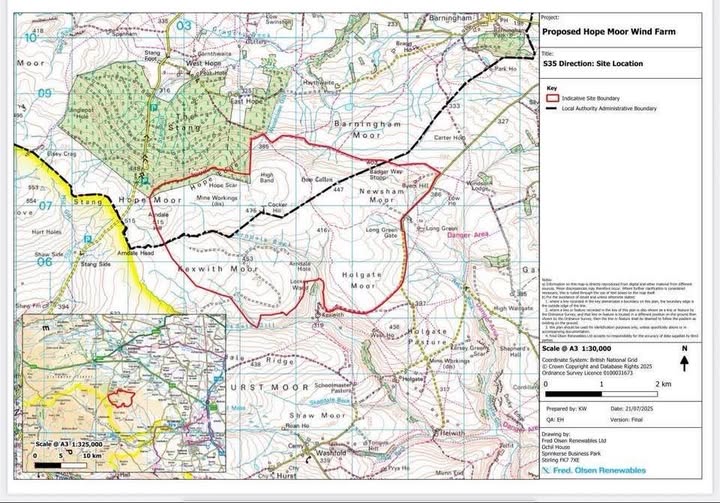

Fred Olsen Renewables are planning to construct a wind farm that would cover more than 11sq.km, including Hope, Newsham, Kexwith, Holgate, and Barningham Moors (see Appendix C). There would be 20 turbines, each one standing roughly the height of Manchester’s Deansgate Square South Tower (see image above) which is the tallest building in the UK outside London, at around 201 metres.

This would be the tallest and densest onshore wind farm in England. It would be positioned between a National Park and an Area of Outstanding Natural Beauty, on one of the highest ridges in Teesdale, bordering on Swaledale. Its visual reach would stretch for miles in every direction, from the Lake District to the North Sea, from Tyneside to York.

However, more important than the visual impact is what this scale of development does to the integrity of the upland system itself — its ecology, environment, and the species that depend on it.

A Nationally Significant Ecological Landscape

During the summer, I often see curlews nearby — flying across the fields or sitting on dry stone walls. They have a distinctive call — one of the sounds of a habitat increasingly under threat from human developments. These moors form one of the last intact breeding landscapes for upland birds left in England, including — from my initial research — eight Schedule 1 species and multiple red‑listed waders. See Appendix A for a detailed list of species in this area that these turbines threaten.

This landscape also supports protected mammals, at least eight bat species, and rare upland habitats such as blanket bog, species‑rich heath, and calcareous flushes. See Appendix B. Its ecological fabric is too important, too fragile, and too interconnected to be industrialised.

Section 35: National Power, No National Scrutiny

Fred Olsen Renewables have effectively sidestepped scrutiny by Durham and North Yorkshire councils by applying for a ‘Section 35’, which means it goes straight to the Secretary of State for a decision. They justify the Section 35 fast‑track by claiming the project is ‘nationally significant’. In terms of power output, that is true. But Hope Moor is nationally significant in another way: it is a stronghold for protected species and priority habitats whose loss would be irreversible. In effect, the developer wants national-level privilege without ecological or environmental accountability. If Section 35 is meant for truly national issues, then this landscape deserves more scrutiny, not less. Calling something ‘nationally significant’ does not give licence to bypass the ecological obligations that come with projects of national importance.

Who Profits, Who Pays

Land Registry documents confirm the estate involved is owned by Sir Ed Milbank, Lady Natalie Milbank, and Lady Belinda Milbank. With twenty turbines on their estate, the family stands to make a significant profit — around £3 million a year or more by my estimate. Their profit is private, but the cost is public. This may be lawful, but is it ethical? The scale of profit both for the landowners and Fred Olsen Renewables makes full democratic scrutiny — and ecological due diligence — essential.

Renewables Yes — Industrialisation No

For the sake of our planet, I want more renewables — offshore, or on sensitively chosen onshore sites where design enhances the landscape. That is why I did not object ten years ago. But Hope Moor is a monstrosity that will devastate both local and national ecology.

This isn’t NIMBYism. It’s a question of excessive scale, siting, process, and motive. Does progress require placing twenty Deansgate Towers on one of the most elevated and sensitive landscapes in the North Pennines? Only public pressure can stop it. The endangered species of this region have no voice — but if this landscape falls, the curlew and many other species fall with it. So, please write to your MP, the Secretary of State, and share this message.

Appendix A: Protected and Priority Bird Species in Teesdale & Swaledale

A. Schedule 1 Species (Highest Legal Protection)

Hen Harrier (Circus cyaneus): Schedule 1; Red-listed. Historically bred in North Pennines; any presence or ranging is a major planning constraint.

Red Kite (Milvus milvus): Schedule 1. Disturbance near nests is illegal; symbol of raptor recovery.

Merlin (Falco columbarius): Schedule 1; Annex 1. Breeds on North Pennine moors; sensitive to disturbance.

Peregrine (Falco peregrinus): Schedule 1; Annex 1. Uses crags/quarries; wide hunting range over moorland.

Short-eared Owl (Asio flammeus): Annex 1; treated as high-sensitivity species. Breeds on moorland; ground nester.

Barn Owl (Tyto alba): Schedule 1. Hunts along meadows and rough grass; sensitive to disturbance near roosts.

Kingfisher (Alcedo atthis): Schedule 1; Annex 1. River specialist; sensitive to disturbance near banks.

Nightjar (Caprimulgus europaeus): Schedule 1; Annex 1. Possible but unconfirmed locally; requires evidence.

B. High-Value Upland Species (Red/Amber Listed or SPA/SSSI Features)

Black Grouse (Tetrao tetrix): Red-listed. Teesdale holds c.30% of England’s population; highly sensitive to disturbance.

Curlew (Numenius arquata): Red-listed. North Pennines hold nationally significant breeding densities.

Lapwing (Vanellus vanellus): Red-listed. Important breeding wader of Tees–Swale meadows.

Golden Plover (Pluvialis apricaria): Annex 1. Key upland breeder; sensitive to turbine displacement.

Dunlin (Calidris alpina schinzii): Red-listed upland race; uses boggy moor mosaics.

Snipe (Gallinago gallinago): Amber-listed; indicator of healthy wet ground.

Redshank (Tringa totanus): Red-listed. Part of the breeding wader assemblage.

Oystercatcher (Haematopus ostralegus): Amber-listed; common breeding wader in Teesdale.

Teal (Anas crecca): Breeds in upland pools; indicates wetland quality.

C. Additional Raptors and Corvids

Buzzard (Buteo buteo): Common but fully protected; part of functioning raptor community.

Kestrel (Falco tinnunculus): Amber-listed; declining nationally.

Raven (Corvus corax): Expanding in North Pennines; indicates wilder habitat.

D. Upland Passerines and River Specialists

Ring Ouzel (Turdus torquatus): Red-listed; steep gullies and moorland edges.

Wheatear (Oenanthe oenanthe): Typical upland breeder on walls and boulder fields.

Whinchat (Saxicola rubetra): Red-listed; declining upland species.

Stonechat (Saxicola rubicola): Common on heather edges and scrub.

Twite (Linaria flavirostris): Red-listed; now very scarce in England.

Skylark (Alauda arvensis): Red-listed; widespread in uplands.

Meadow Pipit (Anthus pratensis): Key prey species for merlin; abundant.

Linnet (Linaria cannabina): Red-listed; uses allotments and rough grass edges.

Common Sandpiper (Actitis hypoleucos): Breeds on stony river margins.

Dipper (Cinclus cinclus): River specialist of Tees/Swale.

Grey Wagtail (Motacilla cinerea): River corridors; sensitive to habitat disturbance.

Appendix B: Protected Non‑Bird Species and Priority Habitats

Teesdale & Swaledale Uplands

A. Legally Protected Mammals

Bats (multiple species — at least 8 breeding in the Tees valley region): All bats and their roosts are protected under the Wildlife and Countryside Act 1981 and the Habitats Regulations 2017. Potential foraging and commuting corridors along moor edges, farm buildings, wooded gills and river corridors.

Otter (Lutra lutra): Protected under WCA 1981 & Habitats Regulations. Present along the Tees and Swale rivers and tributaries. Sensitive to disturbance, water pollution and construction near riverbanks.

Badger (Meles meles): Protected under the Protection of Badgers Act 1992. Setts may occur in wooded cloughs and valley edges. Disturbance, excavation or road construction poses risks.

Water Vole (Arvicola amphibius): UK Priority Species. Present in suitable habitat across Teesdale/Swaledale river margins and wet flushes. Sensitive to hydrological change and disturbance.

B. Priority Amphibians & Reptiles

Great Crested Newt (Triturus cristatus): European Protected Species. Suitable habitat in upland ponds, wetlands and flush systems. Any impact on breeding ponds or migration routes is tightly controlled.

Common Lizard (Zootoca vivipara): Protected species found in heather moorland, rough grassland and stony slopes.

Adder (Vipera berus): UK Priority Species. Occurs in heathland and moor edges; sensitive to habitat fragmentation.

C. Upland Priority Habitats (Highly Sensitive to Development)

Blanket Bog: Annex I habitat and a major carbon store. Covers significant parts of the moors. Highly vulnerable to drainage, track-building, turbine foundations and hydrological disruption.

Upland Heath / Dry Heath: Annex I habitat. Supports grouse, waders, raptors, reptiles and invertebrates. Disturbance leads to long-term ecological change.

Calcareous Flushes & Springs: Nationally rare. Support botanical specialists including elements of the ‘Teesdale Assemblage’. Extremely sensitive to changes in drainage and peat disturbance.

Species‑Rich Hay Meadows & Rush‑Pasture (valley margins): UK Priority Habitat. Integral to breeding success of curlew, lapwing, snipe and redshank. Vulnerable to construction traffic and hydrological changes.

Peatlands (deep peat & peat soils): Carbon-rich soils damaged by excavation, trenching, access roads and drainage.

D. Notable Plants (Teesdale Botanical Interest)

Teesdale Sandwort (Minuartia stricta) — extremely rare: Part of the internationally important ‘Teesdale Assemblage’. Highly sensitive to microhabitat change.

Teesdale Violet (Viola rupestris): Rare plant requiring calcareous soils and stable upland microclimates.

Alpine Meadow‑rue (Thalictrum alpinum): Relict arctic‑alpine species dependent on uncropped flushes and specialist habitats.

Spring Gentian (Gentiana verna): Flagship species of the North Pennines; dependent on limestone grassland and unaltered hydrology.

E. Additional Invertebrate Interest

Marsh Fritillary (Euphydryas aurinia) — possible habitat: European Protected Species. Suitable wet‑meadow habitat exists, though presence must be confirmed.

Northern Brown Argus (Aricia artaxerxes): Priority species associated with limestone grassland, present in suitable sites in the region.

Dragonflies & Damselflies (various species): Indicators of healthy wet flushes, springs and bog pools that could be disrupted by hydrological change.

Appendix C: Site Map